Pittsburgh Panthers' Players Turned Down 1938 Rose Bowl As National Champs, the Money Wasn't Right

- Mark Schipper

- Jul 23, 2021

- 13 min read

Updated: Feb 23, 2025

More than one scandal from college football's gray past has held in to its lurid glow, but what happened in 1937 at the University of Pittsburgh has stayed relevant, too. Back in those days the Panther's upperclassmen had carried out a de facto player's strike in pursuit of higher pay and better treatment from the university, which they saw straightforwardly as their employer, and refused to play in the iconic Rose Bowl game after their demands were rejected.

The incident was a stark example of the sport's transformation from a campus pursuit for the gentlemen amateur to that of a professional entertainment spectacle. Over the course of eight decades we have gone from Pittsburgh players demanding an increase to their compensation packages, to athletes on the precipice of being dealt in on the billions of dollars in media rights that they generate and transitioned into employees with some form of collective-bargaining rights.

Back in 1935, two years before the blow up at Pittsburgh, the Southeastern Conference had begun awarding scholarships in exchange for competing at football. The Southern flagship made its move two decades before the arrival of the NCAA-approved Full Ride scholarship and in the face of vocal objections from around the country. Their justification, which was one of the frankest rejections of hypocrisy in the history of the sport, was that their athletes deserved a form of compensation for the amount they sacrificed and added to the culture of the university.

During that 20-year interim a laissez faire approach to roster construction reigned. It was not that it was legal, either in the spirit or letter of the law, to compensate football players, but the NCAA lacked an enforcement bureau to bring down the hammer from Chicago. Instead, they relied on conferences to police themselves.

Amongst the serious programs arrangements with booster groups led to standardized compensation packages that got players through school with their expenses paid and a modest stipend to keep them in clover. The arrangements varied but generally were as lucrative as an individual school was comfortable providing.

Pittsburgh, with its zealous fanbase and passion for football, wanted a team that could compete with the nation's best every season. The school's leadership, responding to the will of its population, had accepted as the cost of business the academic and cultural compromises that a so-called football factory entailed.

For Pitt the returns on its investment between 1915 and 1937 had been gargantuan, with the program averaging a national title almost every third year for twenty-two straight seasons. They had reached eight overall, including back-to-back championships in 1936 and 1937, when the players decided to make their stand.

When their list of demands, which included a cash bonus and paid vacation time, were rejected by a philosophically reoriented administration, the team refused to travel across the country for a second-straight year to compete in the Rose Bowl. The news, which traveled out of Pittsburgh through a series of local newspaper articles, scandalized the sport.

The players’ decision would lead to the resignation of both an athletic director and the head coach, Jock Sutherland, who was one of the era's most impressive chieftains. In the bitter wake of the fiasco a dominant football program plummeted from championship heights into near obscurity.

But what happened at Pitt could have happened yesterday in college football, and may happen again, in a similar style, in the coming years, as the taboo around athletes sharing in the sport's profits is vaporized from the culture.

THE PITTSBURGH PANTHERS

Dr. John Bain, "Jock", Sutherland, with his squared jaw, strong forehead, and ram-rod straight posture, was a Renaissance Man. Standing on the field in his athletic kit, with his good height and physical power, he looked to be in the foremost ranks of top competitors. But had your first look at the man been his highly professorial school portrait, with his wire-framed spectacles, pin-striped suit and understated smile, you might have had trouble envisioning the athlete.

But that was Sutherland. He was both a distinguished member of the faculty at Pittsburgh’s school of dentistry, where he taught a course on the construction of the bridge and crown, and the coach in charge of one of the nation's finest football programs.

Sutherland was a Pittsburgh man to the marrow. A generation earlier he had played for the Panthers under the immortal Pop Warner. Sutherland won three straight All-American awards from 1915 through 1917 and starred on the 1916 national championship team. That squad, the second of Warner's three national champions, had been nicknamed the Fighting Dentists after more than half of its athletes went on to earn their doctorates in dentistry.

After graduation Sutherland played professionally for several months in the disorganized affiliations that preceded the creation of the NFL in 1920 before he took the top coaching job at Lafayette University. Over five seasons running the historically significant program at Lafayette Sutherland rolled up a 33-8-2 record, which included a 9-0 season in 1921 and the Eastern Collegiate Championship. In 1924 he became a returning hero when he signed on to replace Warner, his coach and mentor, at Pittsburgh.

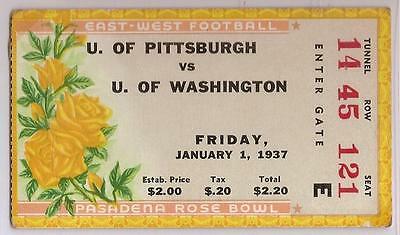

While Warner had been dominant at Pitt, Sutherland was better. He brought home his first national championship in 1929. Three more would follow over the next seven seasons. At the end of the 1936 campaign the Panthers were invited to the Rose Bowl for the fourth time under Sutherland. Pittsburgh had been voted Associated Press national champion before the bowl, but they beat up on the PCC champion Washington Huskies, 21-0, to solidify the selectors' pick.

The Panthers were voted back to back national champions the next year after a 9-0-1 campaign, with the tie coming against the Fordham Rams and the Seven Blocks of Granite anchored by the future coaching immortal, Vince Lombardi. By the end of the 1937 campaign the Panthers were 17-1-2 over their last twenty games, cutting down opponents with a hybrid single-wing offense the newspapers had nicknamed the Sutherland Scythe. They were invited back to Pasadena to defend their crown on New Year's Day, 1938, against the undefeated California Golden Bears.

While the assumption was that no serious football program would turn down the prestige and payout of the Rose Bowl, behind the scenes the relationship between Pittsburgh's program and the university were deteriorating quickly.

It had been the players' experience at the Rose Bowl the year before that made them wary. According to Marshall Goldberg—the two-time Heisman Trophy finalist who had anchored Pitt's Dream Backfield—the miserly administration at Pitt had stiffed the athletes.

While Washington, another program with a highly-organized subsidy system, had sent their athletes to Pasadena in brand new suits purchased by the university, with a hundred-dollars cash waiting in every pocket, Pittsburgh’s players had arrived as poor college students wearing whatever clothes they had in their dorm closets.

“We got nothing but a sweater and a pair of pants,” said Goldberg. “When we showed up for a reception with them, imagine how we felt.”

The players spent the week feeling like working stiffs sent to fetch a $100,000 paycheck on behalf of the university. The shoddiness of the situation led to a memorable gesture from Sutherland, who was known for being extremely cheap with his own finances. Sutherland liquidated the savings bonds in his wallet, collected pocket change from the assistant coaches, and got up about $250 cash, enough to give each player $7.50 folding money. This was during a decade when you could get a good meal at a restaurant for $.50 cents.

When the Rose Bowl organized a trip to the swanky Santa Anita racetrack in nearby Arcadia, the Pittsburgh players pooled some of their cash and set up a series of bets on the horses, hoping to build a bigger pot for themselves to use during the week.

"We all threw in a dollar to make pools to bet with,” said Goldberg. "And we tapped out quickly. You know what it's like to stand around a racetrack with no money?”

The Panthers went on to dominate the game, but the week spent in the San Gabriel Valley, one of the earth's beautiful spots, had been a bummer. So with New Year’s Day 1938 and another Rose Bowl in the offing, the players boiled down their options. The Associated Press's original policy of crowning the national champion at the end of the regular season changed the deliberations. The mythical title rendered a second train ride across the continent less urgent, turning the bowl into an exhibition for its own sake, rather than a championship battle.

The irony of the jam up was that Pittsburgh was arguably the premier "professionalized" program of the era. The situation seemed to be exactly the kind they would be expert at avoiding or controlling before it got out of hand, but the administration at the university under its domineering chancellor, John Gabbert Bowman, was steadily changing its perspective on football.

In his book Pay for Play that covers the history of reform movements in college athletics, author Ronald A. Smith described Bowman’s position:

“Bowman was not opposed to winning football games, but he thought that Pitt was doing it in the wrong way, that was in a professional manner rather than amateur manner.”

Bowman wanted to eliminate the subsidies and stipends, which were the scholarships of the era, elevate the academic expectations, and cut the budget for the program, which included recruiting. The hard-working athletes were caught in the middle. At a climactic moment, with a cross-country trip to the nation’s most prestigious bowl game on the line, the administration dragged a line through the sand.

“Sutherland was a brilliant coach but when he was at Pitt he ran into another brilliant and self-absorbed fellow in Chancellor Bowman,” says Rob Ruck, a tenured professor in sports history at Pitt. “Bowman was fairly autocratic and forceful, but both of those guys saw the university as their fiefdom, and they each were going to determine what would happen and brook no opposition.”

The team meetings held in the weeks preceding the Rose Bowl addressed issues still being battled over today. From excessive practice time to extra benefits that did not equal the players’ contributions, the Panthers could have been arguing with a university administration in 2021. The meetings also demonstrated an increasing awareness of an employer/employee-style relationship that had developed between athlete and university, another issue that is going to reach its climax in college athletics within the decade.

The '37 Panthers were a veteran team with a lot of seniors at the end of three-years worth of sacrifice for the program. They had lost their illusions about the sport as some kind of magical undertaking and had shifted to thinking in brass tacks.

“We were sick of football,” said Goldberg. “Spring practice in those days ran from March to May."

The players exited their meetings with three demands for the school. They admired and respected coach Sutherland, particularly after what he had done for them the year prior with his own money, but they wanted to put the university in a tight spot.

1. That each player received $200 cash—an amount that appeared to be based on the $100 that Washington players got the year before, plus another $100 for the current trip. This was the tail end of the Great Depression and $200 had the spending power of more than $3,000 today.

2. The entire roster would get to travel to Pasadena. Everyone had practiced and contributed to the team, but the year before only 33 of the 66 rostered athletes got to make the trip. This time they wanted to make the three-day train trip as a team. This would double the number of $200 stipends that would have to be issued.

3. A two-week vacation in Southern California after the game. They had won two national championships, brought home a $100,000 Rose Bowl check the year before, and were about to bring home another one. That was the equivalent of around $4.4 million in today's dollars. They felt a gesture of gratitude from their employer was a reasonable ask.

When word leaked on the players-only meetings the Pittsburgh-Post Gazette branded the confrontation a "sit-down strike", making it sound like a true confrontation between labor and capital. The provocative choice in terminology was intentional. It was meant to illuminate the management-labor context that college football worked hard to avoid. When Pittsburgh’s athletic director, Don Harrison, received the list of demands, he said 'No' to everything and told the players to prepare to play.

Harrison’s relationship with coach Sutherland had become increasingly acrimonious. The athletic director had come to believe that because he'd been the one to hire Sutherland that he also was responsible for the coach’s success. Harrison felt Sutherland had grown too big for his hat and dragged him into a power struggle over the football program. When the coach began pushing back against steady cuts and reductions to his operating budget, Harrison warned him to be grateful for what he had.

“I made you and I’ll break you,” Harrison had allegedly told Sutherland.

Immediately after Harrison rejected the team’s ultimatums, Sutherland publicly sided with his players, telling the team he would respect whatever decision they made about the Rose Bowl. At another team meeting, one that included the underclassmen begging to go west so they could experience the Rose Bowl, the upperclassmen voted 17-16 not to return to Pasadena. The team stayed home.

“To our surprise, Jock was jubilant about our decision not to go to the bowl game,” Goldberg later said for a history on Pitt football.

THE DISINTEGRATION OF A DYNASTY

Because the decision to reject a major bowl game had been made by the athletes—and not the school’s coaches or administrators—the news caused a scandal. Harrison, aghast that the players had dug in and won, and isolated on the wrong side of the greatest coach in school history, resigned his post.

Harrison was replaced by a man named James “Whitey” Hagan, who had played on Sutherland's first Pittsburgh teams. But Hagan, despite an assumed loyalty to Sutherland, was hand picked by Bowman to be the friendly face that would sabotage the football program. What had been a behind-the-scenes campaign to gradually de-emphasize football under Harrison became a public one. It was branded with a derisive nickname of its own: Code Bowman.

Bowman always claimed that he did not dislike football, but his jealous and fear of its power on his campus were obvious. Bowman was staunchly opposite the marketing axiom that says a highly-visible, successful football program is the best way to advertise a university. Bowman was embarrassed by the reputation the sport imposed on the university, which the Pulitzer Prize winning author Upton Sinclair once called: "The only high-school in the country that gives a college degree."

While Hagan was dismantling the football program, Bowman was leading the campaign to build on campus a $10 million, 535-foot Gothic tower called the Cathedral of Learning. It was the largest academic building in the Western Hemisphere and was built to be the centerpiece of Bowman's reconfigured university. It certainly is a fine building, and it shoots higher into the firmament than any football stadium ever has, but few souls outside of Pittsburgh know that it exists, and to this day 75,000 paying fans have not come on an autumn Saturday to watch the students go to work there.

Bowman, through Hagan, drained the football budget. Coaches lost their recruiting dollars, players had their compensation packages altered, and the university took scheduling prerogatives away from the staff, an extreme power grab that few coaches of that era would have stood for, and certainly not one like Sutherland, who had brought home seven Eastern championships and five national championships in fourteen seasons. In a matter of months the football crisis at Pittsburgh had become acute.

Near the beginning of the following season Bowman, operating always through athletic-director Hagan, announced that incoming freshmen would not be paid their promised stipends. Instead, they would be required to work full-time jobs outside of practice to cover their room and board at the school. Everyone outside of Bowman's circle was irate.

Athletes felt they had been lured to Pitt under false premises while the Panthers' fans, alumni, and boosters were enraged that their program was being imploded by the school. The Panthers enjoyed the kind of fanatical support that the NFL's Steelers have today. In 1938 Pittsburgh's professional team was called the Pirates, the same as its baseball club, and was a minor affair on its best days. The Panthers were the region's championship avatar, the pride of western Pennsylvania, and a stalwart representative of the strength within the Appalachian land. The idea of shoving football to the back burner because the chancellor felt upstaged on his own campus was a massively unpopular decision.

Predictably, the freshmen players revolted. They refused to pay the tuition that the football program had made a pledge to cover or work full-time jobs on top of the almost full-time job of football. They had signed on with Sutherland under what was in essence a playing contract, and now the university was in breach of its end.

Sutherland stunned the country by resigning the post and walking away in 1938 just one year after winning his fifth and final national championship. He was burned out on battling the chancellor over his football program. Sutherland left with a college record of 144-28-14, with eight Eastern championships, five national championships, and four Rose Bowl appearances, with the fifth trip to Pasadena scrapped by his own players.

Sutherland would coach the Brooklyn Dodgers professional football team for the 1940-1941 season before leaving to serve as a Naval officer for the duration of World War II. He retired from the Navy a Lieutenant-Commander in 1946 and returned home to coach the renamed Pittsburgh Steelers. His NFL teams went 28-16-1 over three years. He stayed with the Steelers for three years, building the first winning teams in franchise history, before dying suddenly of a brain tumor while on a scouting trip in 1948.

Bowman, who believed he knew what was best for everyone, tried to paint a rosy picture of the situation with the football program. The chancellor assured students, alumni, and boosters that Pittsburgh would continue to compete at the top of college football, but this time with a clean conscience and on strictly amateur principles. The Panthers were going to do it the right way. It was a vision only an entrenched, out-of-touch academic could deliver and truly believe. After running up an astonishing record of 171-32-16, with eight national titles over 24 campaigns with Warner and Sutherland, the Panthers dropped to 37-56-2 over the next decade, including 24-straight losses to teams from the Big Ten Conference, which they had hoped to join during better days, and plummeted into irrelevance.

Bowman retired in 1945 after serving twenty-four years as chancellor. Three years later Pittsburgh would re-fire its football program in an effort to reclaim some of its lost glory. By the middle 1950s the Panthers were back in play as one of college football’s better programs. In 1976 they would win the program’s ninth national championship before being engulfed by the Steelers' Super Bowl dynasty and slipping permanently in the city's pecking order.

The startling aspect of the battle over Pittsburgh's football program in the 1930s is that all of the essentials remain with the sport today.

"The scandal of collegiate athletics keeps playing itself every few years in a different form,” says Ruck, the professor. “The NCAA has been so ridiculously slow in dealing with this. Instead of getting out ahead of the curve, they got absurdly behind. I don't know where things are heading, but the blowup of college sports appears to be on the agenda."

excellent work...but the school is the University of Pittsburgh, not Pittsburgh University.