Hayden Fry and Jerry LeVias Made the Southwest Conference Black and White and Shook Up the Old Order

- Mark Schipper

- Mar 18, 2021

- 20 min read

Updated: Feb 4, 2022

By Mark Schipper

THEY ALWAYS MADE GOOD

The young head coach Hayden Fry, and his even younger player, Jerry LeVias, had trust in their relationship because each man had always kept his word to the other. But this moment, standing next to a payphone in the half-bright shadows beneath Memorial Stadium in Austin, with that dull roar and tumult of a fall Saturday rising toward its zenith, was putting their perfect record in doubt.

The coach, who was tall with a heavy jaw and strong chin cleft at the middle, a lot like a football coach ought to look, knew he was not suddenly going to find a quarter for the long-distance call to Jerry’s grandmother. This was the problem, and it was real. The grandmother, the family matriarch, had been guaranteed a check-in before every game for a prayer and blessing as a condition of the grandson’s scholarship, and today they were as close as they ever had been to breaching those terms.

As the stadium clock ticked down toward kickoff, with the window for desperate measures evaporating like dew from a football field on a hot Texas morning, Fry suddenly set off for the concession window in the main concourse. The coach had spotted a member of his university’s marching band milling around while looking at the menu, apparently with a coin in hand and not sure how to spend it. The band member, wrapped in the red and blue dress uniform of Southern Methodist University, saw the prospect of an unusual encounter closing in from the far side of the concourse and stopped to meet the man.

“We sure could use that quarter,” Fry said to the band member in his soft Texas twang. “We can’t play until we make a phone call. I guess we left the change in our other pants.”

The band member, now peering around the coach, could see LeVias, the team’s surprisingly-small star player, standing at the payphone with his helmet off but otherwise fully dressed for the game. There was not enough time to wonder if this surreal scene was just a weird dream, being hit up for change by the football team's head coach and star player moments before kickoff, so the coin was simply handed over with a nod, no questions asked.

“Thank you dearly. You didn’t really want that popcorn, anyway,” said the charismatic and convincing Fry, leaving on a friendly wink.

The coach went back to the player quickly, passing the coin for the call two-hundred-and-fifty miles across the state.

Grandma LeVias, the watchful, spiritual head of the close-knit LeVias clan, picked up the phone at the other end. She is the one who'd convinced Jerry it was his purpose to go to Dallas and SMU to integrate the region’s flagship league, the all-white Southwestern Conference. She had been waiting patiently for the call as the priest waits at the altar to make a blessing.

Quickly, against the final minutes before kickoff, the prayer began for Jerry. Grandmother LeVias prayed he would be kept safe in his righteous battle—as David had in the olden times while facing Goliath—against the organized forces of cruelty and injustice. That was Jerry’s purpose at SMU, according to his grandmother, to help defeat the old and the wrong and, through the power of that victory, usher in a new era of decency and virtuousness. She had the ultimate faith in a just God to see that mission through.

Then the phone changed hands and she prayed again over coach Fry, asking that he too be granted protection and guidance—both today against the University of Texas, and for all time as he carried the fight to those who refused to believe in a righteous cause. Those last, the recalcitrant and hateful, were the ones who ultimately deserved forgiveness and pity because, in grandmother LeVias's words, they walked in a frightening darkness and knew not what they did.

The call was wrapped, the promise kept for another week, and the coach and player moved fast through the tunnel and out onto the field to rejoin their team moments before the opening kickoff.

The star player who, like the ancient hero, had accepted it was his fate to undergo a difficult ordeal so that others may be spared the agony, trotted out onto the field, standing alone in front of all those eyes whose secret hearts he could not know, to field the kickoff.

He wore number twenty-three, and that too was grandma LeVias, who had chosen it for Jerry and made it a second condition of his scholarship. She had picked the number after the biblical psalm:

“The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want . . . . . Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for thou art with me.”

A PLAN SET IN MOTION

Hayden Fry was the reason Southern Methodist University, and not some other Southwestern Conference school, was the first to put a black athlete on scholarship. The courage, fortitude, and talent of Jerry LeVias, with the protection of his grandmother and her God, had brought the campaign to fruition.

Fry, at thirty-two-years-old and without any college head-coaching experience, had compelled SMU, a major program with fleeting eras of immense glory receding further into her past, to come to him. He had hung up on their first offer when he was told black high-school players were off limits as potential recruiting targets. The year was 1962 and SMU was too timid to stand alone in front of their seven peers, six of them neighbors in Texas, with a black athlete on their roster and his education fully covered.

“Nobody in the Southwest Conference has an integrated program and SMU won’t be the first,” the school's administration in Dallas had told Fry.

There was intense racial prejudice to challenge amongst the old guard, the alumni, and boosters—and the college administrators, traditionally timid and conservative on terrain where their jobs and revenue streams are threatened, did not want to lead a hopeless charge into the massed and armed forces of opposition.

In his memoirs Fry wrote that SMU was not a promising job for a young coach, and he would turn it down unless they agreed to integrate. The Mustangs had more than a decade of consistently bad football behind them, and nothing on the near horizon to suggest they could compete with Texas, Texas A&M, or Arkansas, where Fry was a top assistant under Frank Broyles, who had built a reputation as an elite groomer of future coaches.

SMU's world in the early sixties ended at the outskirts of the Dallas-Metroplex area. The Mustangs yearly marker for success was the outcome of the big-rivalry game against a faded Texas Christian University for possession of the Iron Skillet, the schools' victory totem since 1946. The Mustangs had gone 2-9-1 over the last twelve in that series and Fry did not see much growth potential for the program if the status quo had to be protected.

“Was I putting my future coaching career on the line?” Fry later wondered. “Perhaps, but it never occurred to me.”

Black Americans mattered to Fry for personal and professional reasons. Personally, he had grown up in West Texas with black neighbors and friends. He had sweated with them at work and taken his recreation with them after hours. There is little in life more potent than unspoiled, open-hearted youth, and daily proximity to the egregiously mistreated for salting the earth where prejudice otherwise might have taken root.

Fry sat with his friends in back of the bus for the simple reason they enjoyed each other’s company; and he sat with them on the balconies at movie houses because that is where they had to sit, and splitting up for the film was not something kids did when they were out with their friends.

“By the time I reached junior high-school I was genuinely bothered by the way my friends were treated,” Fry wrote.

When they were split up for high school, the friends bussed off to all-black Dunbar while Fry went to Odessa, where he would quarterback the football team to a state championship in 1946, he had seen enough to pledge an oath to himself. Fry swore that if he ever was in a position to shake up the established racial order, he would.

Now, as a football coach, Fry wanted to keep black Americans in Texas. For many decades black scholars and athletes, outcast and exiled on their own soil, had been migrating north, east, and west to study and compete at the institutions that welcomed them. Many exiles had made major contributions to their teams and schools. In the years after the East Coast elite, the sport's founding fathers, had de-emphasized football and backed off of athletic scholarships, the Big Ten and the Pacific Coast Conference had been the beneficiaries of the black exodus from the South. And that too had bothered Fry.

“The opportunity to open the Southwest Conference door to black athletes really excited me,” said Fry, who had descended directly from Texas’s first American families.

Fry's great-great-grandfather had fought with general Sam Houston, who was himself a United State's Senator and the governor of Texas, at the Texas War for Independence. Fry was both conscious of his heritage and determined to demonstrate that the blood line had not attenuated across the decades.

“I knew there were a lot of great black high-school players in Texas and I thought they should have the opportunity to stay home. I was tired of watching them go,” said Fry.

SMU’s great thirst for Fry, who was moving up on coach-candidate lists across the country, can be posited by the school’s second salvo. The administration—well paid, well fed, and safely ensconced in segregated Dallas—had talked over Fry’s proposal and, upon further review, found the terms satisfactory. If forcefully integrating an athletic league that stood shoulder to shoulder in a long defensive line with the Southeastern Conference, maintaining at terrible cost the old-guard Southern Pride, and insistence upon the separation of the races, was what it took to secure his services, then the initiative was his.

The conversations between Fry and SMU were frank from that point on. Fry was not so much advised as warned there would be heavy resistance to his plan. But the coach, who had entered the workforce as a teenage 'nubbins' in the Texas oil fields, and served three years as an officer in the United States Marine Corps after playing college football at Baylor, knew the score as well as anyone. Those were the obvious risks and he would run them. Fry was far more concerned about the young man who would have to walk point for the entire campaign than he was about himself.

On that front, SMU was clear as well. The young man could not be a marginal student or citizen; and he could not be just an athlete. He would have to come from a solid family and be a teenager of immense character and accomplishment, both on the field and off. Any weaknesses in that vessel would be used to rip open a hole and sink it in infamy, they said. Fry agreed with the administration and as he took over the flailing football program in the autumn of 1962, the search began.

Meanwhile, as word leaked out across the league about Fry's campaign, multiple coaches at league's prestige programs stepped forward not to lay groundwork for what was an obvious and inevitable change coming to the region, but to assure their fans, alumni, and boosters that they would not be bringing home black student-athletes any time soon.

Within two years the Mustang’s recruiting trails had taken them two-hundred-eighty miles sou-by-sou-east to Hebert High School, where an athlete of small stature but immense quickness and speed called Jerry LeVias was setting his league on fire.

“When I saw Jerry perform on the field I decided he was the most exciting high-school player I’d ever seen in Texas, and we actively started recruiting him,” coach Fry said.

The Football Was The Easy Part

Doak Walker reigns as the greatest athlete in Southern Methodist history, and remains one of the magical names in the pantheon of American football. Playing in that monster generation that returned home from the battlefields of Europe and the Pacific to attend college on the G.I. Bill, Walker became a star of stars for the Mustangs.

A three-time consensus All-American during his three years as a starter, Walker as a sophomore won the 1947 Maxwell Award as the best all-around player in America. As a junior he brought home the Heisman Trophy as the game’s greatest player, period. The Mustangs won back-to-back Southwest Conference championships in 1948 and 1949 and played in two New Year’s Day Cotton Bowl games.

Over the course of Walker’s scintillating junior and senior seasons, as demand for tickets seemed to grow exponentially, an upper deck was built onto the western side—and then a year later onto the eastern side—of the famous Cotton Bowl stadium at the State Fair grounds in Dallas. The new decks raised capacity from forty-five-thousand to more than seventy-five-thousand souls to quench the voracious demand. Like Babe Ruth and Yankee Stadium, the hugely expanded Cotton Bowl was called “The House that Doak Built” forever after.

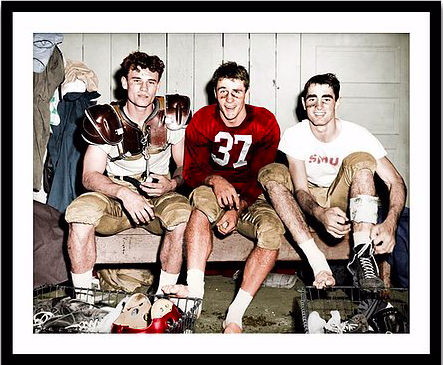

By the middle-1960s Walker was back in Texas and still around football. He carried now the additional prestige of professional glory, having led the Detroit Lions to back-to-back NFL championships in the early nineteen-fifties—with his number thirty-seven set to be retired by the franchise—and enshrinement in the professional football hall of fame still in his future. Walker was coaching a Texas high-school all-star game and LeVias had been assigned to his team.

“He’ll make a good coach out of someone,” Walker quipped to the newspaper boys after watching LeVias during the week of practice.

Walker was right, but he did not know the school would be SMU, or that LeVias, an offensive specialist in the newly reinstated two-platoon football system, would challenge and break several of his own offensive records.

Working in harmony with SMU’s institutional dictates, LeVias came from a big, tight, and deeply religious family. He was a strong student who took academics seriously, and seemed mentally tough enough to stand up to the gaff, as they said in those days.

The completeness of LeVias’s development made him a special person and prospect. He was not exploited by SMU for his athletic ability and hidden from the classroom, he was prepared both for the gridiron and the intellectual rigor of college course work. LeVias had received several major-football offers, most notably from Tommy Prothro at UCLA where his first-cousin, Mel Farr, was a star halfback for the mighty Bruins.

Neither Fry or the SMU administration had attempted to soften the outlook for what was waiting for all of them back in Dallas. Over multiple recruiting visits with LeVias and his family, Fry framed the situation, and LeVias’s role in it, as a Jackie Robinson moment for the Southwest Conference.

Eighteen years earlier Robinson had integrated Major League Baseball and paid a devastating psychological toll from the abuse and hatred he had to absorb from certain racist and reactionary quarters. Professional football had been integrated—except for a disgraceful ‘Gentlemen’s Agreement’ regression from 1933-1945— since its inception in 1920.

Eastern schools had fielded black athletes in the 1880s, while northern schools had followed them almost immediately afterward. Each of those regions were followed in turn by the western institutions as they began fielding teams, with the entire integrated portion of the game picking up momentum throughout the 1920s and 1930s. By the 1960s northern and western schools were playing with black quarterbacks, and in several cases with squads that featured more black starters than white.

But the Southern leagues had circled their wagons and armed for battle, regarding the arrival of black Americans as a threat to their existence, and glowered out from behind their bulwarks with a hostile rage. Segregation and Jim Crow laws were in fact the last stand of the old Confederacy’s rear guard, but it was clear to many the time had come to force the issue directly.

Grandmother LeVias believed Jerry was the one to do it, and SMU was the place where it would be done. So Jerry signed on with coach Fry and prepared to move to Dallas. The plan had moved to its final phase.

ON CAMPUS

LeVias got to campus in the fall of 1965 and played freshman football while establishing himself as a college student, as contemporary NCAA regulations required. Racist fanatics began sending hate mail and death threats to Fry’s office, warning him not to play LeVias on the varsity team, followed by several ugly and uncomfortable confrontations for the head coach at social functions with fans and boosters. Fry knew for a fact that in spite of his status as a native Texan who had played collegiately in the Southwest Conference, if this did not work out he and Jerry were going to be run out of town on the proverbial rail.

LeVias, of course, as a new college student acutely isolated by his race, got it worse than Fry. Despite an active security plan and a system for screening phone calls, LeVias went to class and practiced in the aftermath of racial taunts and insults fired from multiple directions. Several times strangers spit at him and cursed him, leaving LeVias, who had grown up rooted to and protected by his family, hurt and shaken as he returned alone to his single-room dorm to try to study or call home for solace.

After a series of bomb threats was made and then repeated, both the local police and Federal Bureau of Investigation had to open case files. SMU was told to keep everything under wraps rather than make a plea for them to stop, lest any copycats or agents of mayhem be inspired by the attention death threats could bring.

“Jerry was a pretty depressed young man for a while,” Fry wrote in his memoir. “There must have been times he felt like quitting SMU and going to a college where he wouldn’t experience such awful racism.”

“There were times I wanted to quit,” LeVias told a reporter. “My dad told me I gave coach my word.”

But for all of the initial ugliness and hate, which they had expected, it did not take long before LeVias’s classmates got to know and like him. His teammates, who had treated him rough at the outset, ostracizing him and making him feel unwelcome, moved along the same trajectory.

Going into his second season, as he became eligible for the varsity, LeVias had discovered that coach Fry had his back for real. The pair would talk by phone late at night as Fry, who used a West-Texas twang to belie a mastery of practical human psychology, taught Jerry how to deal with people and how to handle himself in these tense situations.

“Hayden's most profound statement to me was, 'Levi, things are going to happen around you and things are going to happen to you, but the most important thing is what's going to happen inside of you,'" LeVias wrote in the forward to Fry's memoir.

"He always believed that if you developed the student, you would get a good athlete. Through him I received an academic, athletic, and social education. He helped me to be the understanding person I am today, and taught me how to deal with the inequalities of life and society."

One day LeVias had entered the football offices while Fry was meeting with an SMU booster. Boosters, depending on their level of clout, temerity, and meddlesomeness, can be the unseen puppet masters pulling strings behind the curtains at college football programs.

Through the thin walls and doors in the office LeVias heard the booster level an aggressive ultimatum at the coach. Referring to LeVias as a racial slur, he told Fry to keep him off the field or he would stop replenishing the athletic coffers with good Texas greenbacks.

LeVias had walked in on what could be considered the ultimate test for a college head coach.

“Coach told him to kiss him where the sun don’t shine,” and threw him out, according to LeVias.

VARSITY CAREER

Fry knew it was strange for a head coach to look forward to early season road games in the far-away Big Ten, but he did. SMU went north in those days in hopes of scoring a massive, early-season upset, and despite all of the added stress of the foreign terrain against powerful programs, Fry said the relief of not worrying about racial taunting on game day was immense. That lurking, dreadful fear of some half-psychotic incident occurring on their home soil took its daily toll on the coach and the player.

When LeVias made his debut on the SMU varsity in 1966, the eyes of Texas, and everywhere else across the South, were on him. And to the shock of everyone outside of maybe coach Fry, those eyes made witness to a sensational string of victories.

The Mustangs, beginning with a week one home upset over Illinois out of the Big Ten, found astonishing ways to win, often late in the fourth quarter and the game’s final moments. Rookie Southwest Conference starter LeVias grabbed touchdown passes against Texas, Texas A&M, Baylor, and TCU—each of SMU’s biggest rivals—on the way to an outright Southwest Conference championship for the Mustangs and an invitation to the Cotton Bowl game on New Year’s Day.

It was SMU’s first conference crown in eighteen seasons—the first since Doak Walker’s 1949 campaign—and it appeared to be some kind of miracle. Fry, in his fourth season, had an experienced, deep football team on offense and defense, but it was the newcomer, LeVias, who'd added something potent to the mix, making electrifying and standout contributions to an offense that built a reputation for big plays in tight spots.

In those days Texas was the conference’s premier football program, but its head coach Darrel Royal had not recruited LeVias—both because he was black, the Longhorns would not integrate until 1970, and because the scouts said he was too small, anyway. Texas was not alone in that physical evaluation. The historically black universities at Grambling, Southern, Alcorn State, and Prairie View A&M, where LeVias had assumed he would play, had not recruited him for the same supposed weakness.

But after he snatched a touchdown pass in the Mustangs 13-12 upset over Texas in Austin, Royal was made a believer.

“Well, he didn’t sound very big when they described him, but he looks plenty big to me now,” Royal said after the game.

LeVias’s athletic brilliance, showcased as it was in front of massive crowds who could not deny its merit, began, as it often does, to thaw the ice separating LeVias from the fans, boosters, and public. This was a bitter irony not lost on coach Fry, who had fought ugly and disheartening battles against the same people just to get LeVias the chance.

“The more touchdowns you score, the whiter you get,” said Fry, who had for the rest of his life kept what happened with LeVias as grist for his own mill.

Following the Southwest Conference title run, SMU graduated its core group and did not win another league championship during LeVias’s final two years, but LeVias played out a brilliant individual career. He was named an All-Southwest Conference player each of his three seasons as a starter, and was recognized as a consensus All-American as a senior.

One of LeVias’s quarterbacks, Chuck Hixon, had nicknamed the receiver “Ol’ Flypaper Hands” because the football seemed to stick fast when it hit them. Higher praise from a quarterback to a pass catcher does not exist.

Coach Fry remembered that the hundreds of young kids around the program, the youth football players and children of alumni and season ticket holders, loved LeVias. They wanted to be around him at the public events and to absorb some of his magic by osmosis. LeVias’s was by far the most requested autograph on the team.

“Don’t kids have great instincts?” wrote Fry.

While the kids were fine, some of the adults and SMU opponents were locked in their own embarrassing personal struggle. For LeVias the daily grind around Dallas over four years included multiple smaller incidents, but never became the dreaded big blow up that everyone most feared. LeVias simply played through whatever petty taunts and open hate he encountered. His three years as a varsity athlete were marred by only one serious confrontation during a game—an incident that sparked a moment of blind rage in LeVias’s senior season that almost undid some of what he had worked so hard to build.

After knocking LeVias into a pile up with a hard tackle during the Iron Skillet game against blood-rival TCU, a Horned Frogs’ player had held him down, addressed him by a racial epithet and tore off his helmet before spitting in his face. LeVias had fought his way up, shouted something at the player that Fry said he could not hear from the sideline, and went to the bench where he threw away his helmet and quit.

“If I had a gun, really I would have shot somebody,” LeVias said years later about the on-field assault. “I lost it, and I dared anybody to touch me.”

But it did not last. Coach Fry left his post on the field-edge of the sideline and found LeVias on the bench, his head down, difficult to console. Fry admonished LeVias in clean, clear West-Texan, not to get his dauber down and, more importantly, not to let the other guy find his goat and get it. Composure would get him through this trial as it had the others. These were some of the fundamental commandments in the Church of Fry, and their real-world applications.

“I had to learn West Texas,” LeVias said when he first got to campus. “I didn’t know what in the world he was talking about. What’s a dauber? I’m looking to see if my pants are zipped up.”

By his senior year LeVias had learned the gospel and, more than that, he had become a believer.

Back on the field, as TCU prepared to punt early in the fourth quarter with the game tied at fourteen, LeVias knew he had to be the one to return it. Jumping up from the bench and heading toward the field, LeVias told Fry he was going to return the kick for a touchdown. Fry responded that it sounded good for their side, but recommended he come back for his helmet first, which LeVias quickly did. He then took his place, alone again under the spotlight, and waited to execute one of the most harrowing charges in the game of football.

LeVias, like Fry, always kept his word. He caught the punt cleanly at his own eleven-yard-line, reversed field multiple times and eluded what coaches later said were eleven attempted tackles, dangling like a stunt driver through traffic, while returning the kick eighty-nine yards for what turned out to be the game-winning touchdown.

The Mustangs kept the Skillet—21-14—and left TCU without anything to spit on but themselves.

“Like Babe Ruth, he called his shot, making the most spectacular punt return I’ve ever seen,” wrote Fry.

But to this day LeVias looks back at that return, and that moment, as a missed opportunity. He had violated both his grandmother’s sacred injunction and his own personal code of conduct.

“That was one of the worst touchdowns that I have ever run in my entire life, because I did it out of hate,” LeVias said. “Hate does not hurt the other person as much as it hurts you.”

“I don’t have any animosity in my heart for them because as my grandmother use to say, ‘Bless them for they know not what they do.’”

In his three years as a pass-catching specialist, LeVias broke multiple of the great Walker’s receiving records. In his final college outing at the 1968 Blue Bonnet Bowl, in poetic fashion, he hauled in the game-winning pass to upset the powerful Oklahoma Sooners on New Year's Eve. That Southwest vs Big 8 matchup had become a major national event because of its status both as the first bowl game played on New Year’s Eve, and the first-ever played indoors, as it was staged at the brand new, and sold out, Astrodome in Houston. Beyond the massive stadium a big television audience found out live and in color what the Southwest Conference had known for years about the strong medicine wielded by the great LeVias.

Off the field LeVias had been an academic All-American, and graduated in three-and-a-half years with a degree in marketing.

“We had certainly chosen the right person to integrate the conference," said Fry. "As a football player, he never missed a game; as a student, he may have never missed a class."

“I know there were some bad times for him, but I can’t be fully aware of his feelings because I am not black. And I’m sure he experienced abuse I wasn’t aware of. I admire Jerry LeVias more than any player I have ever coached,” Fry wrote in his memoir.

LeVias was taken in the second round of the NFL Draft and played five superb professional seasons, becoming an AFL All-Star and leading the Houston Oilers in every offensive scoring category. But with several prime athletic years left he grew tired of the game, worn out because of his smaller stature, and retired to go into business, where he had planned to make his living all along.

But our story does not travel down that road. After the principles had gone on their own personal journeys for nearly forty years, everything circled back, as it often does, to where it began.

It was the summer of 2003, with Fry now five years retired from coaching, and LeVias still in business in Texas, when the call came for both men as the College Football Hall of Fame announced they would be inducted in, side by side.

"We started this journey together," LeVias said, "and it concludes tonight. It means everything to be in the same class with him.”

“The best thing I ever did was give Jerry LeVias a scholarship,” said Fry, who had gone on to do many great things in his profession, including the capture of three Big Ten titles at the University of Iowa.

The sun rose and set on sixteen more seasons before Hayden Fry was called home to God, as the LeVias clan understood it. Surrounded by words of praise and tribute, the memorials and retrospectives—from Iowa and Big Ten country where Fry had become a true legend of the sport—to Texas, where everything had started—LeVias took the stage at a large gathering of family, friends, and so many of Fry's former players, to speak in memoriam of his old coach.

“Levi, he called me when he loved me. And when I was in trouble, he called me Jerry. But I knew him as a coach and a father figure,” LeVias said, his words catching with emotion as they were amplified over the crowded grandstands. “Coach Fry was a great man and he was one of God’s greatest gifts to a lot of us. May he rest in peace and God bless him and I’ll love him forever.”

If you want to think about making a difference in the world, of leaving it a little better than you found it, you might take as your example Jerry LeVias and his old coach, John Hayden Fry, who walked through the valley together and feared no evil, even when they did.